In early

1917, the United States had not yet entered World War I, but war clouds were

beginning to form for the country. From April, when America would finally enter

the war, until November of 1918, the so-called “War To End All Wars” would take

American lives, cost American treasure and consume most of America’s attention

for the next two years. Although daily life in America continued, the war’s

effects tinged virtually every aspect of American society. Before the war’s

end, Major League Baseball’s very survival would come in to question. For Eddie

Foster and baseball, World War I would change a lot over here.

1916

marked Washington Senators infielder Eddie Foster’s fifth season with the team,

and it had been his worst year as a Senator to date. His batting average in ’16

was a measly .252, and his hitting really tailed off near the end of that

season. Also, Foster played more games in the field at second base in 1916,

where he was not accustomed to playing and therefore not as comfortable in the

field, than any other season in his career. Late in the year in 1916, there was

even talk Foster would be traded to the Browns, as there had been for several

years prior1. On November

7, 1916, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that the Browns sought to trade second

baseman Del Pratt2, third

baseman Jimmy Austin3 and

outfielder Ward Miller for Eddie Foster and Senators second baseman Ray Morgan,

Foster being the main player sought by St. Louis. On February 7, 1917, the Browns

owner said he was going to attend the American League Winter Meeting in Chicago

to “acquire a third baseman, either Fritz Maisel or Eddie Foster.” On February

8th, the Browns decided that Washington Senators Manager Clark Griffith

“would not let them have Foster,” so the Browns pursued a different third

baseman. Through the tumult of trade talk and potentially lower wages, Foster

remained sanguine, telling the Washington Times in late 1916 that that he

“cares little for Stove League gossip anyway.” Foster went on to say “I hope

Teacher4 signs me up

again, for it’ll be terrible not to be signed and have to play ball just the

same.”

While war

clouds were forming for the country as a whole in 1917, they were beginning to

recede for baseball itself. The “baseball wars” had come to an end when the Federal

League had folded. As a result of the death of the Feds, baseball players lost

playing options and bargaining leverage and Major League owners therefore began

chatter amongst themselves of cutting back ballplayer salaries. However, the

Baseball Fraternity5, the

euphemistic name for baseball’s first players’ union, threatened to strike

after an adversarial ruling from the National Baseball Commission6. The biggest complaint of

the Fraternity, headed by attorney and former baseball player Dave Fultz7, was that players could be

cut and not have their contracts honored after being injured. The Number One complaint

that precipitated the threatened 1917 strike, though, was that Fultz and the

“Fraternity” wanted minor leaguer ballplayers to be provided transportation to

their teams’ camps the same way that Major League teams did for their players. The

threatened strike fizzled when most big name ballplayers ignored Fultz and

signed contracts anyway.8

Eddie Foster, a member of the fraternity since its inception, was in the second

year of a two year contract at the time and his remarks made to Evening Star

sportswriter Denman Thompson were probably representative of most Major

Leaguers at the time:

“I believe in the organization… and think its

members should stick to it when it’s in the right, but it does look as if the demands

being made now are a little unreasonable. The major league players are not

concerned over the points at issue, already having been granted everything the

minor league players are already contending for, so why should they take any

action that would hurt themselves as well as the major league owners, whom they

admit have treated them fairly and have met all their demands?”

When

America entered the war later in 1917, the “Fraternity” dissolved, along with

any threat of a player strike in the future.

In January,

Eddie Foster and his wife came back to Washington after spending a month

visiting Eddie’s mother and family in Chicago for Christmas. When he arrived in

Washington, Foster got back into his yearly routine of training at the local

YMCA prior to leaving for training camp. In 1917, he worked out each day at the

Y in February and March to “lose ten or twelve pounds of superfluous

flesh.” In prior years, Washington’s Manager,

Clark Griffith, had even had his pitchers do “gymnastics” at the Y before camp,

but in 1917 he decided he was “dubious about the benefits to be derived from

such a procedure,” preferring instead to work them hard at camp instead. Griffith

also refused to consent to having his players inoculated against typhoid, even

though he understood “…what the result would be if one or more of his men were

stricken as Eddie Foster was a couple of years ago.9 Nevertheless, Griffith “…considers it inadvisable to

take preventative measures at this time.” Anti-vaxxer sentiment is apparently

not a new thing.

1917 was

the first year that the Senators had training camp somewhere other than

Charlottesville, VA.10 Griffith

moved the Senators training camp to Augusta, GA, to take advantage of warmer

March weather. Foster rode the train

with Griffith down to Augusta on March 8th, and, if you believe

Evening Star correspondent Denman Thompson, engaged in some minor law breaking:

“Griffith plans to have each of his men take

down a quart of alcohol for rubbing purposes, Trainer Mike Martin being unable

to buy the liquid in Augusta, owing to prohibition laws.”

Picture Caption: Prohibition started in November 1917 in the District of Columbia, well before it started in the rest of the nation.

Interestingly

enough, although it was the Senator’s first training camp in Augusta, it was

not Eddie Foster’s first training camp in Augusta. In 1910, Eddie Foster made

the Yankees (then still known as the New York Highlanders) roster at their

training camp in Augusta. Foster’s stay with the Yankees would not be a long

one, though, due to his future teammate, Hall-of-Famer Walter “Big Train”

Johnson. When the Yankees played in Washington on April 22nd, 1910, Walter

Johnson pitched against the Yankees. That day, the Big Train was having trouble

locating his pitches. When Foster came up to bat, Johnson hit him in the ribs

with a fastball, sending Eddie to the hospital.11 Foster evidently tried to play through it in

subsequent games, but Foster’s batting average dipped so low afterwards that

the Yankees sent him down to their minor league team, Rochester, where Clark

Griffith eventually found him.

The

entire Washington party seemed to enjoy Augusta. The weather was good and they

found the local folks extremely hospitable, the only real complaint being the

food. The great Ty Cobb made his home in Augusta at this time. He would

occasionally pop by and watch practice or visit with folks associated with

Washington’s team. Cobb even had Clark Griffith over for supper one evening.12 Interestingly, Cobb

played all his minor league ball before the Majors in Augusta, and the

Washington scribes got some great stories on Cobb’s time as a minor leaguer

there:

“Cobb came to the Augusta team with the dirt

between his toes. At that time the club was in the hands of a fellow inclined

to bet on the games, and not always on his own team. One day he had his money

on the visitors and Cobb came to the bat with three men on the sacks. Ty was

given instructions to tap an easy one to the infield, but, instead, cleaned up

with a three-bagger. He was fired right then and there.”

Cobb was

of course hired back shortly thereafter because Cobb was so good that even his

gambling fool minor league team owner couldn’t keep him off the team. Another

good tidbit was that:

“Cobb surely was a green youngster when he

first came here. He used to take a ball of popcorn along with him to the

outfield, and would munch it all during the game. When a fly ball was hit out

his way, or he had to retrieve a hit, he would drop the popcorn and attend to

his duties. As soon as the task was over, he would begin eating the popcorn

again.”

Although

America was still officially neutral in March 1917, war sentiment exploded in

February when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare on American

shipping and the Zimmerman Telegram was made public. To demonstrate baseball’s

patriotic bona fides (read: garner good PR), show that soldiers were willing to

serve in the war too (read: keep the government from shutting organized

baseball down during military conscription) and to set a “good example for

others in military preparedness,” the American League’s owners13 decided at their winter

meeting in February 1917 to have their baseball teams perform military drills

during training camp, with a competition later in the season in which the best

drilled team would receive a $500.00 dollar (about $10,000.00 in today’s money)

prize. Each team was assigned a drill instructor by the military. On March 10th,

Washington’s drill instructor, a corporal in the Army named John Dean, arrived

in Augusta to give the players “military instruction and training.” Dean was

evidently very earnest in what he hoped to accomplish with the players.

According to the Evening Star, “Corp. Dean is of the opinion that guns will be

provided for the use of the players here, but says baseball bats will do if no

rifles are available.” In fact, the drills initially consisted of the players

marching in formation with baseball bats held on their shoulders as if the bats

were rifles. In Augusta, the players practiced their military maneuvers for at

least one hour every day. On March 12th, “The start of the first drill

was delayed for some minutes by the tardiness of Eddie Foster” [and two other

players] “who did not reach the park until 10 o’clock and had to don their

uniform before drilling. The trio was threatened with a term in the

‘guardhouse’ if the offense is repeated.” The military drills continued each

morning for the rest of training camp and every day for the rest of the season.

Washington’s drill instructor, Corporal Dean, traveled with the team all summer.

When talk came up late in training camp that some other AL teams didn’t want to

drill, Clark Grifith voiced strong approval for the drills, saying “The country

faces a crisis and it will find every baseball player loyal to the core.”

As had

been the case for much of 1916, Foster found himself playing second base rather

than third in training camp. Foster did not hit well in the scrimmages against

a squad composed of minor leaguers and reserves called Yannigans that the team

played every spring. It wasn’t for lack of work, however: “Eddie Foster already is practicing at place hitting, for which he has

an enviable reputation. Each of the men is allowed to two balls in practice and

Foster invariably hits the first into left field and the second to right. Eddie

is not hitting them far, but is getting a good hold on the ball and sending it

on a line over the infield.”

Although

his hitting was slow to come around, Foster’s play in the field almost always

sparkled. “Foster has not started to hit as he should, but handles the chances

given him at second base better than [Carl] Sawyer14 does.” “Eddie Foster has few, if any, peers when it

comes to getting the ball away from him quickly.” “At second, in the games

here, Foster is taking the ball on bad hops and throwing to bases from all

conceivable positions, with not an instant’s hesitation.”

On March

22nd, training camp closed up and the Senators’ starters left for a

barnstorming tour of the Mid-South, starting in Birmingham, where Washington

played the Barons and beat them 4-2. From there, the Senators went to Memphis,

where they played the Memphis Chickasaws (or Chicks for short). Foster walked

and scored a run for Washington in this game. On Sunday the 25th,

Washington played an exhibition game against the Cincinnati Reds in Memphis

before a crowd of about 6,000. The Reds’ manager at this time was Hall-of-Fame

pitcher Christy Mathewson. Griffith had managed the Reds in the past, so he was

motivated to beat Cincinnati any time one of his teams played them, exhibition

game or otherwise. Foster again walked and scored, and Washington beat the Reds

5-1. Earlier that morning, one of Foster’s teammates got the authentic Memphis

experience:

“George McBride was the victim of a sneak thief

some time early Sunday morning. While he and John Henry, who was rooming with

him, were asleep, someone entered their room and rifled McBride’s clothes,

removing $20” (about $400

in today’s money) “in cash and several

stickpins from his pocketbook, which was later found empty in the bathroom.”

The team

then left Memphis and arrived in Nashville on the 26th. The Washington

Herald reported that Griffith gave the team a talking to when they arrived,

upset that they only had 13 hits as a team so far on the road trip. According

to The Herald, however, the players all decided that 13 must be their lucky

number, since:

“The Griffmen’s special was due to arrive here

at 3:00 A.M., but the old Louisville and Nashville schedule shows a three-hour

delay. Two freight trains had a head-on smash-up about eighty miles out of

Nashville, and if it had not been for a twenty minute delay in getting away

from Memphis the Nationals’ squad would have been one of the principals in this

head-on collision.”15

The

Senators exhibition game against the Nashville Vols16 was rained out on the 27th, but Washington

beat the Vols 6-3 on the 28th, with Eddie Foster getting two hits in

that game. Despite the rainy weather, a

relatively large crowd was on hand, no doubt due to the fact that Foster’s

Senators teammates, the Milan brothers (outfielders Clyde and Horace), were

from Linden, TN, which was “within auto riding distance of Nashville,” and to

see Walter Johnson possibly pitch, if only for a few innings. “Zeb”17 [Clyde Milan] “told

Manager Griffith today that the entire town – or as much of it as could be

transported on wheels – is planning to be on hand to see Zeb and his ‘roomie,’

Walter Johnson, in action. Zeb asserts that the fans in his section are rabid

to a degree, and that, in view of the fact that all the moonshiners thereabouts

will be included in the party, a right noisy delegation should be in evidence.”

On March

30th, the team went to Louisville, KY. While there, the team visited

the Louisville Slugger facility. “The result of the visit to the bat factory

here yesterday was an order for some three dozen sticks of various shapes and

weights, including two ‘police billies’ for Eddie Foster.” While in Louisville,

the team played the Reds in another exhibition game, this time losing 5-4. On

the 31st, the team moved on to Cincinnati and played the Reds again,

this time winning 5-4. Foster singled and scored, but also made a throwing

error that contributed to a big inning for the Reds.

In the

wee morning hours of April 3rd, the team finally ended their trip

and rolled into Washington. “High priced hotels ruined the financial piles of

everyone in the party. The club this spring picked out the best hotels on the

road and the players, drawing no salaries, suffered accordingly. Laundry bills

were heavier than usual. Tips were needed on every side, and by the time the

boys reached Cincinnati, they were cleaned… it was a light crowd that emerged

from their cars this morning at Union Station.” The team continued to practice

and do military drills, and played exhibition game against Georgetown and the

Philadelphia Phillies on 7th, both of which Washington won. Foster

had an RBI against the Phillies. After the Philadelphia game, the team ran off

the field to catch a train to Columbus, OH.

From

Columbus, the Senators went to Philadelphia to play Connie Mack18 and the A’s for opening day

of the 1917 regular season. Before the game, the A’s baseball team put on a military

marching spectacle. Although the general consensus is that the convention of

playing the national anthem at sportings event started in the 1918 World Series,

when it was played during the seventh inning stretch, it would seem that the

anthem was being played before games prior to that time. For instance, that day

in Philadelphia:

“It is doubtful there was a single one of the

7,478 who paid their way to see the 1917 curtain raiser yesterday who did not

feel a little thrill when Old Glory was lifted to the top of the flagstaff in

Centerfield by a delegation of four of the Mackmen. The entire squad of local

players, marshalled by… their military instructor, marched from home plate to

the flagpole, preceded by a band, and to the strains of the national anthem,

the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ was hoisted aloft, while every person in the

inclosure stood with bared heads and cheered.”

That day, military recruiters were active in the stands, which were draped everywhere with bunting. Eddie Foster played second base and batted second in the lineup. He went hitless that opening day, but Walter Johnson pitched and Washington won 3-0. The next day was a different story for Foster. Foster had three hits, one of which was a triple, and drove in two runs in another 6-2 victory over Philadelphia. One Washington sportswriter wrote that “It’s the mystery of baseball that Eddie Foster doesn’t bat .330 or better each season. Nobody in this country can place the ball or engineer the run and hit better… Pitchers love him like they do sore arms.”

Washington proceeded to lose the last game of their series in Philly and were then swept in New York by the Yankees. On the 20th, the Senators came back to Washington for their home opener. As had been the case in Philadelphia, pre-game involved patriotic displays of military marching by the team. Clark Griffith and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt then led the team out to the flagpole that had just recently been installed in the outfield. Griffith and FDR then hoisted the flag up the pole as a military band played the National Anthem. Vice President Thomas R. Marshall then threw out the first pitch from his seat behind home. Washington lost to the A’s again that day, 6-4 in 13 innings. Foster had two hits in the game and drove in the tying run with a sacrifice fly in the 10th. Washington took two out of the next three, splitting the series with the A’s. Washington lost to the A’s 4-3 on the 23rd, but Foster drove in two runs that day.

Although

the team was not doing particularly well, Foster individually stayed hot at the

plate through the end of April in to early May. In the midst of Foster’s

hitting outbreak, Clark Griffith waxed philosophical to sportswriter Denman

Thompson one morning in Boston:

“I have had the three greatest place hitters

of the game on my teams19, and I want to tell you that Eddie Foster

is the best. The others are Willie Keeler and Hal Chase. Willie taught Hal, and

Hal taught Eddie. Foster is the smartest batter I ever saw.

A pitcher usually can tell by the position of

the batter’s feet just where he hopes to hit, even as a boxer gets a good line

on the plan of his foe by watching the latter’s feet. If you see the right-hand

batter’s feet set for an attem

pt to hit to right field you can pitch inside,

and nine times in ten he will pop in the air. So it goes.

But you can’t do this with Foster, because he

shifts too late for the pitcher. The hit and run with a man on second, or with

men on second and first, is a play which Hal Chase excelled, probably does yet.

You see, the shortstop would be edging over toward second to hold up the runner

and the third baseman would be over nearer his bag for the force on a bunt,

leaving a big space between him and the shortstop. Chase could bang the ball

through that hole better than anyone I ever saw, but Foster can do it just as

well.

It’s fairly easy to tell about the way to hit

and run, but it’s the most difficult thing in the world to teach a man to get

that snappy motion, foot-shifting and balance, which all place hitters must

have.”

As soon

as the war began, so did the government’s efforts to raise money to pay for it.

Questions also began almost immediately about whether organized baseball would even

be able to continue. In the spring, as part of its war tax bill, Congress

proposed a 10% tax on all baseball tickets costing 40¢ or more. Even concession

stand workers and credentialed news media were required to pay an admission tax

to get in the game. The proposal was evidently so controversial that the Ways

and Means Committee in the House refused to even hold hearings, although

Johnson and his American League owners lobbied individual congressmen

separately. Ban Johnson was quoted in early May as saying that if the War Tax

went into effect, the league would have to call off the 1918 season. However,

Johnson and the owners were undercut in their lobbying efforts by Chicago White

Sox owner Charles Comiskey,20

who voluntarily gave 10% of the gate from the White Sox’s first ten home games

of the 1917 season to the Red Cross. Although Comiskey could afford to do this,

due to low attendance and war factors, the other American League owners could

not (or, at least, that’s what the other owners claimed). The so-called

baseball tax did eventually go into effect, and stayed largely unchanged until

1928. Despite this, Johnson assured in the press that the 1917 season would

play until completion, but ominously said that “If the country is still at war

in the following spring no attempt will be made to begin another season, and

the ballparks will remain closed until the return of more peaceful times.”

As the

calendar flipped into May, Foster’s hitting began to cool off somewhat, and the

team’s record stayed under .500. Despite that, 1917 was a year that had a lot

of noteworthy occurences for Foster and the Senators. On May 13th,

Washington was in Cleveland to play the Indians. The game was a pitching duel,

Cleveland getting only two hits off of Washington’s pitcher that day. In the 3rd

inning, a controversial balk, called after Eddie Foster had tagged out the

baserunner at third and after Cleveland’s star center fielder/coach, Tris

Speaker21, complained to

the umpire, led to Cleveland’s first run. In the 7th inning, Speaker

got the Indians’ second hit of the day. He was at second with one out when a

hit and run was called. Washington’s shortstop that day threw out the batter at

first easily, and as Speaker tried to score the first basemen’s throw beat him

to the plate. Washington’s catcher blocked the plate and Speaker slid around

him, missed home “with his toes at least a foot” and never touched the plate. When

the umpire called Speaker safe, “the entire Washington team came in to tell him

about his eyes and plenty of other things that wouldn’t sound well in Sunday

school. Even Eddie Foster chipped in with a few unkind words.” According to The Evening Star, the umpire

“…was so clearly and absolutely wrong on the

play that even Eddie Foster, who seldom registers a protest, no matter what

happens, was all wrought up. Foster was the first player to reach McCormick

after the ruling and threw his glove down in disgust when McCormick refused to

reason with him. Play was suspended for five minutes while the Washington athletes

stormed and raved.”

Two of

Washington’s ballplayers were ejected from the game. According to the Washington

Times, Foster “joined his mates in kicking and had to be waved back to his

position twice.” Later in the season after another controversial umpiring

decision in another game, the Washington Times had this quote: “It is a saying

in the American League that whenever Walter Johnson or Eddie Foster kick, the

umpiring must be rotten.” No matter how mild-mannered and reasonable people are,

bad officiating/umpiring can turn even the best of us into enraged maniacs.

Umpiring

in the dead ball era was a difficult and often times violent proposition. On

June 23rd, the Senators began a one month road trip with a

doubleheader against the Red Sox in Boston. The Red Sox’s starting pitcher for

the first game that day was Babe Ruth22.

Washington second baseman Ray Morgan led off for Washington. After the third

pitch was called a ball and the count was run to 3-0, Ruth yelled to home plate

umpire Brick Owens23, “If

you’d go to bed at night, you [expletive deleted], you could keep your eyes

open long enough in the daytime to see when a ball goes over the plate.” Brick

told Ruth he’d throw him out of the game if Ruth didn’t pipe down. Ruth yelled

back, “Throw me out and I’ll punch you right in the jaw.” Owens called the fourth pitch (reportedly

thrown right down the middle) ball four and Ruth charged Owens. Ruth missed his

first punch, but connected with the second. A melee then ensued around home

plate, and it took Boston’s manager and several policeman to drag Ruth off the

field. Ruth would eventually get fined by the league and suspended ten games

and was forced to issue a public apology.

After

Ruth was ejected, the Red Sox brought in Ernie Shore24 to pitch. Eddie Foster, second in the lineup that

day, then came to bat. In the melee, Boston’s starting catcher had also been

ejected. With a new pitcher (who was not given very long to warm up) and a new

catcher in the game, Washington’s Ray Morgan, on base because of the walk, decided

to try to steal.25

Boston’s new catcher threw Morgan out a second. Shore got the second batter,

Eddie Foster, to ground out, and then proceeded to throw a complete game

no-hitter, recording 26 straight outs to get a quasi-perfect game. In the

seventh inning of Babe Ruth and Ernie Shore’s no-hitter, with a man on at

second, Shore hit an easy ball back to Washington’s pitcher, who had the runner

at 2nd hung up, was undecided where to throw. He threw late to the

shortstop covering 2nd, but the baserunner had taken off for 3rd.

The shortstop rocketed a throw to Foster, who evidently couldn’t handle it, and

both runners were safe. The middle finger of Foster’s right hand was dislocated

attempting to handle the throw to 3rd. Foster had to leave the game

and was out for the next ten days. Washington went on to be shut out of both

games of the doubleheader that day.

Picture Caption: Boston's powerful 1917 pitching staff. Babe Ruth is 2nd from left; Ernie Shore is 2nd from right.

Eddie

Foster returned to the lineup on the 4th of July for a doubleheader

against the Yankees at the Polo Grounds in New York. Starting second baseman

Ray Morgan was out with an injury, so, as was often the case that season,

Foster had to play 2nd. Eddie Foster seemed to have a habit of

playing his best games on holidays such as Memorial Day, the 4th of

July, and Labor Day, and also on days where there were big crowds on hand in

the stands, such as Opening Day and weekends when folks were off work (baseball

stadiums did not have lights at this time, so games were played in the

afternoon or early evening when people were still at work). July 4th,

1917, would be just such a game for Foster, who announced his return to the

lineup by going 3 of 4, driving in two runs and scoring twice himself in the

morning game of the doubleheader. Washington swept the Yankees that day and

then split a doubleheader with the Yankees the next day, but Washington would

struggle for the rest of their road trip afterwards.

On July

7th, Foster got good news. The Washington Herald reported:

“Somewhere between Washington and Detroit,

Eddie Foster, the Nationals’ second baseman, yesterday got a telegram that gave

him more joy than a circuit smash with three on. ‘A darling little Foster and

she’s a girl,’ was its text. Mrs. Clark Griffith, in announcing the arrival of

the latest suffragist, said that everybody was happy and doing well. Eddie may

take a day off and come and shake Miss Foster’s hand. Otherwise he will be on

the job as usual, but getting the latest returns from the home grounds every

few hours.”

As far

as I can tell, Foster did not take any days off from playing to celebrate his

first child’s birth, probably because, as stated before, the team was in the

middle of a MONTH LONG road trip at the time (they stopped by in Washington

after playing the Eastern Seaboard teams). Tragically, Eddie’s first child, little

Nancy Foster, died only a little over two years later in August of 1919. The

news item announcing her death in the Washington Times said “the child had been

ill for about ten days, spinal meningitis finally coming to end its sufferings.”

On July

15th, Washington played the eventual 1917 World Series champion

White Sox in Chicago. There was a large crowd of about 20,000 on hand that day.

The weather was warm and Eddie was playing in his hometown, so, true to form,

he had a big day. In the 2nd Inning, Foster walked and eventually

scored. Morgan was still out with an injured leg so, as he had to do often

during the course of the 1917 season due to injury and Griffith constantly

juggling his lineup to improve the Senators’ perpetually light hitting, Foster

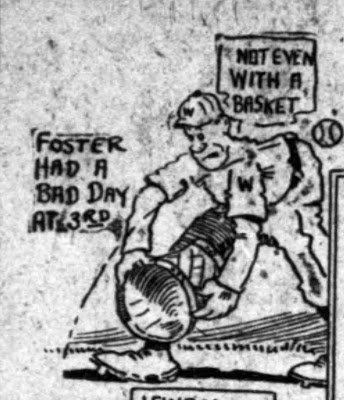

was playing second base instead of third that day. In the 4th

Inning, an easy pop fly was lifted in Foster’s direction. Eddie proceeded to

handle the pop up “as if it were a trench bomb,” dropping the ball and allowing

the Sox to score the tying run. Washington came in to the top of the 9th

trailing 4-2. The Griffs rallied, though, and tied it. With two out and two on

and the game tied, Foster “caught one on the end of his bat and drove it to

deep left,” driving in the game winning runs. As the Washington Post put it, “Eddie

Foster believes in making amends for mistakes, and he did so with a vengeance

this afternoon.” In the bottom of the 9th, Washington brought in

Walter Johnson to close the game. With the Sox already having one run in and

the score 6-5, Shoeless Joe Jackson came to bat with the bases loaded. He lined

out to Johnson and Washington held on for the win on what could’ve been a big

day for Chicago, if, as the Chicago Tribune put it, Foster hadn’t “spoiled the

whole afternoon.”

In 1917,

Washington Manager Clark Griffith joined in the patriotic euphoria and decided

to donate balls, bats and other baseball paraphernalia to soldiers going

overseas. The effort gradually grew into Griffith’s “Bat and Ball Fund.”

According to one Washington sportswriter, raising money and getting the

supplies together made Griffith “the busiest man in nine counties.” To help

raise money, Griffith had bat and ball days in every Major League park, in

which buckets would be passed around and fans would be exhorted to donate. The

doughboys in France and Belgium did indeed play a lot of baseball; makeshift ball

fields dotted the countryside behind the fighting lines, and military leaders

like Pershing considered sports like baseball excellent for morale and physical

preparation. The first shipment by Griffith’s fund of baseball equipment to

Europe was put on a steamer named the Kansan,

which was sunk by a U-boat in July 1917. Eventually, hundreds of thousands of

dollars (millions in today’s money) worth of baseball equipment would

eventually make it over there.

Besides

being known for the hit and run and slick fielding at 3rd base,

Eddie Foster was also known for breaking up no-hitters late in ball games. For

example, in August 1916, Foster broke up 42 year old St. Louis Browns pitcher

Eddie Plank’s bid for a no hitter with one out in the ninth inning.26 More on poor Eddie Plank

shortly. On July 20th, 1917, Eddie Foster again broke up a no-hitter

in St. Louis in the ninth inning, this time against Dave Davenport. For the

first eight innings, the closest anyone on Washington’s roster had come to

getting a hit had been Eddie Foster himself earlier in the game, when future

teammate Johnny “Doc” Lavan robbed him with a leaping catch of Foster’s line

drive. Foster led off in the ninth. With the count 0-2, Foster refused to chase

a curve, and on the next pitch, poked one into right field for a hit. St. Louis

Star Times columnist Clarence Lloyd noted the similarity to the game the year

prior, “only Foster didn’t use a fungo stick.27 He picked out the thickest bludgeon in the Washington

heap and crashed a bona fide blow to right. This upset Dave and he permitted

two more hits to follow,” before George Sisler saved the day with some

incredible plays in the field. As St. Louis sportswriter L.C. Davis wrote in

his Sport Salad column:

“Oh Davy, dear, you very near

Pulled off a no-hit game;

You came within an eye-lash

Of the well-known hall of fame.

But in the ninth Ed Foster

Stung the pellet for a base

And, in a way of speaking

Slammed the door right in your face.”

At the

end of their road trip on July 23rd, Washington’s record had

bottomed out at 17 games below .500 and they were in last place. As they played

at home for a month, though, the Senators played better ball and their record

began to improve. On August 6th, Washington hosted the St. Louis

Browns.28 On the mound that

day for Washington was future Hall-of-Famer Walter “Big Train” Johnson. On the

mound for the Browns that day was none other Gettysburg Eddie (future

Hall-of-Famer Eddie Plank), whose no-hitter Foster had so unceremoniously

broken up about a year earlier. The crowd on hand that day was larger and

louder than normal for a Monday game between two bottom dwelling teams due to

the 500 DC National Guard soldiers in the stands. The Guardsmen’s section in

the stands that day had “a bugler, a cheer leader and the vocal power peculiar

to a college rooting section at a football game.” The game was a pitching duel,

tied at 0 through nine innings. Washington’s best chance to score in the

regularly allotted nine innings came in the 3rd, when the leadoff

man singled and then stole second. With one out and a man on second, Plank

walked Eddie Foster intentionally. The next batter flied out and then Horace

Milan was unintentionally walked to load the bases. Browns’ second basemen Del

Pratt (Roll Trotsky – see Endnote 2) then made a diving stop of Sam Rice’s

grounder and threw to first while lying on the ground to get Rice for out

number three.

While

Johnson overpowered the Browns’ batters with his fastball, and both pitchers

had great fielding behind them, Gettysburg Eddie used guile to blank the

Griffs:

“Plank had considerable fun yesterday watching

the efforts of the Nationals to judge his slow ball. He occasionally varied it

with a slower ball, a wide, slow curve and a fast one, straight over, all of

which he delivered with practically the same motion. In the ninth Plank floated

the slowest of the slow up to the plate, and, seeing that Rice was going to

bunt, Severeid” (the Browns

catcher that day) “left the catcher’s box

and ran out into the diamond to field it, reaching a spot several feet in front

of the plate before the ball got to Rice. Sam missed it altogether, Umpire

Nallin’s chest protector stopping its flight. This so amused Plank he delayed

the game for a minute or two laughing over it.”

According

to another sportswriter, Plank laughed so hard when the ball he pitched hit the

umpire that he “had to lie down on the grass for several minutes.”

The game

went into extra innings still tied at zero. Until the 11th, Plank

had only allowed three hits all day. Gettysburg Eddie wasn’t laughing when

Washington catcher Eddie Ainsmith29

led off with a walk for Washington in the bottom of the 11th. Walter

Johnson fouled out for the first out of the inning,

“…but left fielder Horace Milan drove a single

to left field and Ainsmith hustled to third. And when Ainsmith beat Shotten’s

throw to third, the yell those soldier boys let out – if it had been heard

‘somewhere in France’ – would have scared a lot of lads on Kaiser Bill’s team

out of their underground bunks…”

That

brought up Eddie Foster, who proceeded to once again torment poor Gettysburg

Eddie:

“Foster then demonstrated that Plank knew

something when he passed him earlier in the fray, with a man on second base…” “And

then Pop30 Foster, who has been long on fielding but short on

batting since the club returned home, sent the ball skipping merrily over

second base. Ainsmith skipped just as merrily home, and it was all over – even

the shouting.”

Washington

had won, 1-0 in 11 innings. A few days after the game, Plank left the team

while there was still a month and a half left in the regular season to back to

his farm in Gettysburg. August 6th in Washington turned out to be Eddie

Plank’s last game as a Major Leaguer. Plank gave his reason for retiring as

“the strain of baseball was telling on him, causing trouble with his stomach.”

A pesky place hitter like Eddie Foster is just the kind of guy who could give a

pitcher an ulcer.

In early

June, Clark Griffith had taken virtually the entire team to register for the

military draft. On August 7th, Foster and two of his teammates were

drafted into the Army. However, Foster was able to claim an exemption due to

having two dependents, a wife and child. On August 17th, Foster and

first baseman Joe Judge were granted an exemption from the local draft board

and “needless to say, the wives of these ballplayers were made happy by the

news. It will be a good piece of news for Manager Griffith, as these boys are

among the stars of the Washington club.” Foster’s teammate, future Hall-of-Fame

right fielder Sam Rice31,

would not be so lucky and Rice wound up serving over there in 1918.

The

competition for best military drilling for an American League baseball team

began on August 21st. A committee composed mostly of military

officers, led by Major General Henry P. McCain,32 was appointed by American League President Ban

Johnson to judge all the teams. The committee visited four American League

cities that week to judge each American League team (home and away) playing the

day of their visit. On August 23rd, the committee was at Comiskey Field in Chicago

to judge the Senators’ and the White Sox’s military drilling. According to the

Evening Star, when it came time for Washington’s portion of the program,

“The Griffmen were on their mettle and, ably

handled by Sgt. Dean, put up a snappy exhibition, remarkably free from even

small, technical mistakes. The accuracy with which they executed squad

movements and the machine-like precision with which they handled their ‘guns33’

elicited spontaneous approbation from the thousands of uniformed men as well as

the fans. Lieut. Col. Raymond Shelton, U.S.A., complimented them on their fine

showing and said he considered them a very well drilled team.

An event not on the program was the collapse of

Eddie Foster near the close of the drill. Foster and Clyde Milan both were

seized with cramps early in the morning coming over on the train from St. Louis

and were unable to sleep… When Foster arrived at the park from his home, where

he stays while in Chicago, he was apparently very ill and was advised not to

try the drill, but insisted on going on the field. Near the end of the

maneuvers he fainted and had to be assisted from the field. Neither Foster nor

Milan was able to play in the game that followed the military and flag raising

maneuvers… Their illness was diagnosed as ptomaine poisoning34, but

neither was able to account for how it was contracted.”

Foster

was taken to his mother’s Chicago home to convalesce. When he woke up the next

day, Foster had no memory of even being on the field the day before. Foster

stayed in Chicago while the Senators continued on their road trip to Cleveland.

Foster did not get back in the lineup until Washington played the Yankees in

New York on August 31st, eight days later. He lost around ten pounds

from the illness. Washington swept the doubleheader that day. Naturally, Foster

drove in two runs in the 11th of the 2nd game. The St.

Louis Browns, of all teams, won the military drilling competiton and the $500

prize; Washington finished third.

After

his return from illness, Foster got hot at the plate in September. Washington

played much better down the stretch, finishing the 1917 season only five games

below .500 and in fifth place in the standings. As was often the case in the

teens, Washington’s biggest problem was that they lacked good hitting and had

almost literally no power. The rash of injuries and illnesses suffered by the

team and the lack of depth on their bench doomed Washington to a lower finish

than they probably deserved. Outside of his rookie year and his final year in

the league, Eddie Foster’s .235 batting average for the 1917 season represented

Foster’s worst year at the plate as a professional. Still, in the dead ball

era, a .235 average was good for fourth place among American League third

basemen that season.

In

December 1917, Clark Griffith, in an effort to try and get more hitting for the

team in 1918, traded pitcher Bert Gallia and cash considerations (he gave the

Browns $15,000.00, which would be about $300,000.00 in today’s money) in cash

to the St. Louis Browns in exchange for shortstop Johnny “Doc” Lavan35 and outfielder Burt

Shotten.36 As the

calendar flipped to 1918, Foster’s two year “baseball war” contract (negotiated

while the Federal League still maintained a tenuous existence) with the

Washington club was up. Foster signed another contract with the club in

January. Although salaries were being cut across the league due to expiring

contracts and dwindling attendance on account of the war,

“… it was hinted that the cut in salary handed

‘Fatima’ 37 was a very slight one. Eddie has always been a player that worked

heart and soul for the club which he was representing. Foster, during the past

few years, has been a fixture with the Nationals, as he is a player who has

always been in shape and has given the best he has in him.”

The

Senators had their training camp in Augusta, GA again in 1918. Unlike the year

prior, this time the weather was much rainier, beginning from the very first

day the ball club arrived. Bad weather would plague the team all spring right

up until Opening Day. Augusta was particularly soggy that spring. Practice games

and exhibition games were repeatedly rained out. The team even practiced in the

rain one day. And of course, the Senators went through their military marching

drills each day regardless.

As

usual, Foster came to camp in good shape. On the second day of camp, The

Evening Star noted:

“Despite the strenuous matinee yesterday, there

was no let-up work today. All the players, with the exception of McBride,

Foster and Milan, are being driven at a smart pace to get the soreness out of

their limbs. These veterans, along with Johnson” [and several others] “are being given wide latitude in their

training, as they know how to proceed to get in condition the best and quickest

way.”

Considering

how Foster and the team started the 1918 season, Clark Griffith probably wished

he had driven them a little harder.

One

feature of that spring was that the Senators would often play soldiers in exhibition

games. For instance, a large crowd showed up in Augusta to watch Washington

play the 108th Field Artillery Regimental team on March 23rd.

According to The Evening Star, the soldiers “got an eyeful of Major League

Baseball as presented by the Washington club, and a laugh a minute from Nick

Altrock, who acted as announcer, umpire and coach for both teams. Washington

won 9-2 and “Foster showed the Sammies some fielding which earned him cheers.” Afterwards,

many on Washington’s team hung out with the soldiers at their mess hall in

Augusta Heights. On the 27th, Foster had two hits and a stolen base

when Washington played the 110th Infantry from Camp Hancock. Foster had three hits

and a sac fly when Washington scratched out a 4-0 win against the 112th

Infantry later that month.38

The

Senators left their training camp in Augusta on April 3rd and headed

North to play two exhibition games with the minor league Atlanta Crackers. On

the way up, according to the Post, the players got another taste of what war

time baseball would be like:

“Each player will have to carry his uniform in

a roll as he will on all trips this summer. Well paid athletes will have to use

their hands to carry something besides their bats in a game and hands to grip

somethings besides a baseball this season. And there won’t be a lower berth for

all the big leaguers either. Players who never rode in an upper when someone

else was footing the bill, will have that experience.”

Washington

won both games against the Crackers. They then proceeded to Chattanooga to play

the Lookouts, but both of their exhibition games with them were rained out.

According to the Post, “The rain has

enabled them to take it easy, pinochle to their heart’s content and sleep late.

Some of them had planned to take a trip to Lookout Mountain this morning to

look over the historic spots in the vicinity. They are more interested in base

hits than in history, but then ball players believe that old saying about when

in Rome do what Romans do.” The Senators then went back down to play the

Crackers again, but that game was rained out too. Washington played two

exhibition games against the Phillies in Camp Jackson (Columbia, SC) and Camp

Sevier (Greenville, SC), losing the first and tying the second. The Senators

then proceeded North to play another exhibition game against Philadelphia in

Norfolk, VA, on April 12th, but that game was snowed out, so Foster

went to Fredericksburg to visit his wife’s family.

The

Senators opened the 1918 regular season at home against the Yankees on April 15th.

The Yankees won 6-3. It was not a good day for Foster; he committed an error

that led to a Yankee run, went hitless and hit into a game ending double play

in the bottom of the ninth, killing a potential rally. Washington won the

second game of the series, but lost the third game to the Yankees when Foster

dropped a throw from the catcher to third to get the man (Del Pratt) being

sacrificed from 2nd to 3rd; darkness prevented the bottom

of the 12th from being played and the Yankees were given that win.

Foster’s work at the plate to start the season was absolutely abysmal. Through

four games, Foster was 1 for 17 at the dish, and he committed several errors.

Washington

then proceeded to lose a home series against Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s,

who were not a good team in 1918. On April 22nd, Griffith was

already juggling his lineup in order to do anything to get the team to hit a

little better. Griffith benched starting 2nd baseman Ray Morgan and

moved Foster to 3rd base for that day’s game and dropped Foster to 7th

in the batting order. Morgan, as it turned out, was one of several Washington

players who were sick with “the grippe”39

in the spring and early summer of that season, which may be at least a partial

explanation why Morgan and the rest of the Senators played so terribly early on

in the season.

Washington

then went on a three city road trip to New York, Boston and Philadelphia, going

4-6 on the trip. Foster missed the next to last game of the road trip with “stomach

trouble.” This seemed to be the turning point of the season for Foster, who

came back the next day for the last game of the series and went to work with

the stick, banging out several hits in an 11-6 Washington victory over

Philadelphia.

Through

his first ten games, Foster had made nine errors. Foster and his team were not

playing well. However, on May 7th, Washington came back home for a

three game series with the eventual World Series champion Boston Red Sox. Washington

won the first game of the series 7-2, thanks in large part to Walter Johnson

shutting down the Sox (the Sox only two runs came off a moon shot of a home run

by Babe Ruth). Foster got a hit and a walk and scored a run in this game. On

the 8th, Washington pounded the Red Sox 14-4. In noting Foster’s

rapidly improving hitting, sportswriter Denman Thompson wrote:

“… yesterday [Foster]

topped it off by registering three singles and a walk in addition to making one

of the swellest barehand stops back of third base that has been witnessed on

the local lot in many a moon. “Fatime” got a great hand from the crowd on

appearing at the plate in the sixth after his spectacular stab and responded by

plunking a hit to left that started Mays [one of Boston’s pitchers that

day] on his way to the sheltering

confines of the shower room. Foster will be a prime favorite with the fans if

he will continue to show some of the pep which has characterized his work the

last three days.”

Foster

made another great defensive play in the seventh inning that day, when a hit

ball took a funny hop and “Foster would’ve been without a few teeth if he

hadn’t gloved it.”

Washington

played the Red Sox in the final game of the series on May 9th. Babe

Ruth pitched for the Red Sox against Walter Johnson for Washington. With the

two teams’ pitching aces facing off, the game was a pitching duel going into

the bottom of the 7th inning, with Boston holding a 1-0 lead.

Washington took the lead in the bottom of the 7th 2-1, but the Sox

tied in the top of the 9th and took a 3-2 lead going into the bottom

of the 9th. Leading off in the bottom of the 9th, Ray

Morgan walked and advanced to 2nd when Foster beat out an infield

hit. Another walk loaded the bases and a sacrifice fly from Walter Johnson tied

the game. With one out in the top of the 10th, Babe Ruth doubled.

Ruth then attempted to steal 3rd base, but he was “cut down in

artistic style” when Washington catcher Eddie Ainsmith threw to Foster,

“Ainsmith’s peg being true and Foster’s touch deft.” In the bottom of the 10th,

with one out and the bases loaded, Foster lifted a fly ball to left field, sacrificing

in the winning run. Despite pitching well and going 5 for 5 at the plate (a

triple, three doubles and a single – Walter Johnson himself went 3 of 4 that

day with a sac fly that tied it), Ruth was the loser. As the Post put it,

“Eddie Foster played another of his old-time

games yesterday. He batted .500, with two hits in four times at bat, and turned

in the sacrifice fly which scored Shanks with the winning run in the tenth. He

also fielded his position faultlessly, accepting six chances without an error.

His one-handed catch and tag of Ruth on Ainsmith’s peg in the tenth when the

slugging pitcher attempted to steal third was a great bit of work, and he

deserved all the cheers he received.”

After

sweeping the Red Sox, Washington played .500 ball against the Indians, White

Sox, and Tigers, going 6-6-1 in their long home stand against those teams. Also

during this long home stand, however, Washington was swept in a four game series

by, of all teams, the ultimately last place St. Louis Browns. This put the

Senators five games under .500 for the season by the time they left for their

first long road trip in late May. In the midst of their long home stand, on May

19th, the Senators played Cleveland in what was the first Sunday baseball

game40 played in

Washington. The crowd of approximately 17,000 was the largest crowd to watch a

baseball game in Washington to that time. Walter Johnson and Stanley Coveleskie41 faced off in a pitcher’s

duel. Washington pulled out a 1-0 win in 12 innings that day.

Foster’s

play both at the plate and in the field really picked up in May. On May 14th,

in the midst of Washington’s long home stand, Washington lost to Cleveland 4-2.

Foster doubled and scored a run that day. In the 9th inning, Foster

walked but was stranded on base when the last Washington batter popped out. May

14th was noteworthy because it marked the beginning of the longest

hitting streak in Eddie Foster’s career, and the longest hitting streak in the

majors in 1918. Some milestones that occurred during Foster’s streak included

Walter Johnson’s marathon 18 inning victory 1-0 over White Sox on May 16th,

a game in which Foster had the second hit for Washington… in the 8th

inning. The aforementioned first Sunday baseball game in Washington on the 19th,

happened during Foster’s streak. Foster did not drive in many runs during his

streak, and he was often stranded on base after his hits. There were also quite

a few low scoring extra inning games, which was a feature of this season for

Washington. For example, on May 24th, Washington played a Red Cross

Benefit game against Detroit, a game in which Foster did drive in a run. Woodrow

Wilson was on hand that day for the first nine innings, but the result was a 2-2

16 inning tie game called due to darkness. Foster drove in a run on the 26th

in Washington’s 4-0 win over Detroit, a game in which Ty Cobb injured

himself racing in from left field and leaping head first to catch Foster’s

short fly ball off the top of the grass.42

As is often the case with ballplayers, when Foster did well at the plate, he also

did well in the field. Yet for all that, Washington couldn’t do much better

than go about .500 during that time. On June 3rd, Foster’s hitting

streak ended in Cleveland in a game Washington won.

On May

23rd, to boost draft numbers and get the nation on a total war

footing, Provost General Enoch Crowder, a Judge Advocate General who was

essentially in charge of administering the draft, issued what came to be known

as the “Work Or Fight” order. The Work Or Fight Order was an interpretation of

the Selective Service Act that required men to either work in “essential

industries” by July 1st or be subject to the draft, regardless of

whether their local draft board had exempted them or not. Under Crowder’s

order, the organized sports of baseball, boxing, and horse racing were not

considered “non-useful,” while actors, opera singers and people involved in the

movie industry were considered “essential.” Almost immediately, confusion over the

“Work Or Fight” order arose, as the government gave conflicting signals about

how it was to interpreted. On the day the order was issued, Secretary of War

Newton D. Baker said “… it was agreed that the question could not be disposed

of until all the facts relating to the effect upon the baseball business has

been brought out through a test case.” American League President Ban Johnson, always

accommodating toward the government, said “I do not believe the government has

any intention of wiping out baseball altogether, but if I had my way I would

close every theater, ball park and other places of recreation in the country

and make the people realize that they are in the most terrible war in the

history of the world.” This pro government position in regards to the war draft

would eventually get Ban Johnson in hot water with his American League owners.

Meanwhile, still more trouble was brewing for

organized baseball. At this time, whenever the President of the AL and the NL

butted heads, the vote of the Baseball Commission’s Chairman would break the

tie. Inevitably, the Chairman’s tiebreaking vote would inevitably leave one of

the league presidents aggrieved. A frequent flashpoint between the two leagues

began to arise when players would sign with multiple teams.43

In 1918, the problem flared up again. A pitcher

named Scott Perry was sold by his minor league club to the Boston Braves.

However, the deal wasn’t officially completed and while he was on the

ineligible list, Philadelphia A’s owner/manager Connie Mack got interested in

him and signed him. As Perry began to have success with the A’s, the Braves

made a claim on Perry through the National Commission were awarded Perry on a

2-1 vote. Connie Mack then broke an unwritten rule of baseball and sued in

state civil court to enforce the A’s contract with Perry. On June 17th,

Mack got an injunction against from a court in Ohio against the Baseball Commission

for Perry to stay with the A’s. Later that summer, the National League

President resigned in protest and National League owners, in an uproar, began

talk of the baseball equivalent of war - cancelling the World Series and

splitting the two leagues again. The National League owners appointed a new

President, and the new NL President worked out a compromise to mollify his

owners whereby Mack had to pay the Braves for Perry. These events would

eventually cause MLB to ditch the Commission system and appoint a single

Commissioner to adjudicate disputes.44

Although

he attended training camp with the team in 1918, future Hall-of-Famer Sam Rice

was ordered to report to his unit by the draft board before the regular season

started. Although Burt Shotten did an acceptable job in right field that

season, Washington dearly missed Rice’s bat in the lineup. However, on June 19th,

Rice got a one week furlough and got in to the lineup to play for Washington

against the Yankees and the A’s. Washington went 4-2 in the six games Rice

played for them that week. In Rice’s farewell game on June 24th,

Rice drove in Eddie Foster with the winning run against the A’s. Shortly after

Rice’s furlough ended, his artillery unit shipped out first to England and then

to France for training. His unit was about to be shipped to the front when the

war ended in November.45

On June 23rd,

near the end of Rice’s furlough, Washington finally came home from another of

their month long road trips. The Senators’ record at this time was right around

.500. Washington then proceeded to sweep a 5 game home series from the

A’s. On June 28th, Washington

began another four game home series with Babe Ruth and the Boston Red Sox with

a 3-1 victory. That day, Washington’s pitcher, Harry Harper46, threw a one-hitter. Boston’s one hit was a towering home

run hit by Babe Ruth. Foster got a hit and scored a run in that game. On the 29th

and 30th, Boston returned the favor, beating Washington each day by

the identical scores of 3-1. In the final game of the Red Sox series on July 2nd,

Eddie Foster had a nice day, while Babe Ruth had a miserable one. In the first

inning, Foster doubled and then scored when Ruth (playing center field that

day) fumbled a ball hit toward him. Later in the game, Foster walked and scored

another run. In the sixth inning, Ruth struck out looking on three straight

pitches, despite being ordered by his manager to execute a hit and run. The Red

Sox’s manager then benched Ruth and fined him $500 (about $8,400.00 in today’s

money). Washington won 3-0. After the game, Ruth went home to Baltimore and in

a fit of pique he told the press that he was considering joining a shipbuilding

league.47 Boston’s owner

traveled to Baltimore and smoothed things over enough for Ruth to rejoin the

team a few days later. Although Ruth did well the rest of that season, the

seeds had been sown for him to be traded to the Yankees.

As the

July 1st deadline for the Work Or Fight Order came and went, ballplayers

kept playing baseball and the season continued. Predictably enough considering

the mixed signals given at the time the order was issued in May, local draft

boards across the country issued contradictory orders on whether or not

baseball was an “essential industry.”

The vast majority of draft boards continued to exempt ballplayers that

had already been declared exempted. However, on July 11th, after the

local District of Columbia Draft Board ordered Washington catcher Eddie

Ainsmith to get essential work or be drafted, Ainsmith, with the help of Clark

Griffith, appealed his local board’s decision to the War Department. On July 19th,

Secretary of War Newton D. Baker ruled firmly against Ainsmith and declared

plainly and unequivocally that baseball was not an “essential industry.”

Baseball owners immediately began lobbying Baker and the Woodrow Wilson administration

to be allowed to finish the season. Eventually, a compromise was settled upon –

the season would be cut short by one month and a temporary week and half

exemption would be granted to the pennant winning teams to play the World

Series early, in September.48

On July

19th, late in the Senators game against the Chicago White Sox in

Washington, word spread of Baker’s decision on the interpretation of the Work

Or Fight Order. Washington trailed the White Sox 5-2 that day going in to the

bottom of the ninth. According to The Washington Times, conversation broke out

amongst Washington’s players as it came time for their at bat in the bottom of

the ninth.

“’What’ll Griff do, go to France with the

Y.M.C.A.?’ asked Mister Foster to George McBride, one of the four eligible.

‘Guess I’ll hook up with ‘em myself. I stand in pretty good at the Y.’”

‘Wait till I come back!’ said George, ‘I’ve got

to go out and get a hit.’

And he did, for he was starting that

ninth-inning rally.”

With the

bases loaded and one out, Foster got a hit and drove in his friend George

McBride to make the score 5-3. A base hit by Washington first baseman Joe Judge

drove in two more runs, tying the score at 5 and sending Foster to third. With

two outs, veteran Frank Schulte came to bat. “Schulte’s single that let Foster

romp in was all that was needed to close the pastime.”

Washington’s

win on the 19th put them four games over .500. From then until the

end of the season, the team played good baseball. On August 15th, in

the midst of Washington’s nearly one month and final road trip of the

abbreviated season, Washington had an off day in Cleveland. Clark Griffith

owned horses, and horse racing was big in this time. According to the

Washington Post, the entire team except for Eddie Foster went to see the horse

races in Cleveland that day. Foster’s refusal to go was no doubt anchored in

his strong evangelical faith. At some point in the past two or three years

prior, his wife took him to a Billy Sunday revival, at which Eddie Foster was

saved. From that point on, Foster became a holy roller. Foster was an usher at

Billy Sunday revivals and often took his teammates to hear Sunday speak. In

early 1917, at the suggestion of Washington’s trainer and “Mayor of Cherrydale”

Mike Martin, Foster himself began speaking to Sunday School classes and other

religious gatherings all over the city. After speaking to his first church, one

Washington newspaper wrote “After hearing Eddie Foster preach, and he does very

well, too, we are convinced he is a better ball player than evangelist.” By the

summer of 1917, Foster evidently became more comfortable speaking to audiences.

One newspaper piece entitled “How Eddie Foster Struck Out The Devil”, said the

following:

“’You can’t be neutral. It must be either Christ

or the devil for yours,’ Eddie Foster, the Nationals’ infielder, admonished his

auditors in the mid-week service at the Washington Heights Presbyterian Church

last night. Eddie was carded as the principal speaker of the evening, and the

little Griff infielder told with a ‘punch’ how he forsook the ‘bright and

breezy highway’ for the ‘straight and narrow.’

Relating his experiences since ‘hitting the

trail,’ Foster spoke of the many excuses he had heard offered by what he termed

‘side-steppers’ from the church. ‘Too many hypocrites in the church,’ said

Eddie, ‘is the reason they gave for not affiliating with it. But, believe me,

better a short time with a few hypocrites in church than an eternity in hell

with a whole bunch of them.’

Foster sketched briefly his wayward career

before succumbing to the ‘great appeal’ first considered by him in a Billy

Sunday meeting, contrasting his former weakness with his present strength

against worldly temptations.”

As the

season came to an abbreviated end, Washington played its best baseball. The

team wound up finishing 72-56, good for sixteen games over .500 and a 3rd

place in the American League standings that season. Washington finished only 4

games out of first. There are a lot of what-ifs with this team. What if they

hadn’t a lot of bad weather in training camp? What if most of the team hadn’t

gotten sick with the flu? What if the team had played only just OK to start the year? What if the season hadn’t

been shortened by war, just as the team was playing its best baseball? What if

the team hadn’t lost its Hall-of-Fame right fielder to the draft?

But by

far the most maddening aspect of Washington’s near pennant miss that season was

the one other American League team most directly responsible for it. You see,

that year Washington had a winning record against all but one American League

team. In a supreme irony for Eddie Foster, the one team that kept Washington

from winning a pennant that season was the bottom-dwelling St. Louis Browns. The

Browns “waxed fat and sassy at the expense of the Griffmen,” going 2-9 at home

and 6-12 overall against the Senators in 1918. If Washington could’ve just gone

one game above .500 against St. Louis, they would’ve played in the World Series

that year against the Chicago Cubs. Instead, the Red Sox did.

Statistically,

1918 was a good year for Eddie Foster. He had the longest hitting streak in the

league that year. He also led the league in at bats and hit for a solid .283

batting average. For a short time in September, Foster played for a team of

“all stars” that Griffith put together to play exhibition games against

soldiers.

Although

it’s not completely clear that he did so, most likely Foster joined his fellow

draft eligible but deferred teammates at “essential” work with the Alexandria

Shipbuilding Company for at least a short time (Clark Griffith took the

essentially the entire team to sign up to work with them on August 20th)

after playing for Griffith’s team in September.

As it happened, World War I ended only a little over two months after

the 1918 baseball season ended, so if Foster did work at the shipyard, it

probably wasn’t for long. On March 9th, 1919, Foster is listed as

having a seat on the board of directors of the newly formed General Auto Truck

Co. “Eddie Foster, when not playing with the Nationals, will spend most of his

time demonstrating the new trucks. This will probably be Foster’s last year on

the diamond.” We know he worked somewhere that winter, though, because when he

reported to training camp in Augusta in 1919,

“At the pilot’s suggestion the midget third

sacker knocked off work a month ago. Juggling heavy sacks of cement all winter

had him worn down fine, but the lay-off packed on about fifteen pounds. Now the

reducing process the work here entails will not leave him thin and drawn.

‘Foster right now is in better shape than he

has been any spring for the last four years,’ Griffith observed. ‘I never saw

him look better.’”

That war

was over, and it was time for Eddie Foster and baseball to start again.

Endnotes:

1) Prior to the 1916 season, the Browns needed a

third baseman and the Senators needed a pitcher, so the Browns proposed to

trade their veteran and future Hall-of-Fame pitcher Eddie Plank for Eddie

Foster straight up. Plank was nicknamed “Gettysburg Eddie” because he was born

and raised and had a farm in Gettysburg, PA. There’ll be much more about

Gettysburg Eddie later in this article.

2) Del Pratt would later be a teammate of Eddie

Foster with the Boston Red Sox. Del Pratt played football and baseball at the

University of Alabama in 1908 and 1909 (he transferred in from Georgia Tech). Pratt

was the first University of Alabama athlete to play Major League Baseball. Pratt

was a fullback and kicker for the Tide’s football team. Pratt’s field goal

against Tennessee in ’08 gave Bama a 4-0 win over the Vols (field goals counted

four points in those days). His athletic career at Bama was cut short in his senior

year (the 1909 football season) due to “faculty trouble.” Pratt studied law at

Alabama, but never became an attorney. He was, however, the Browns’

representative in the Players’ Fraternity. In 1917, Pratt and a teammate

(Johnny “Doc” Lavan – more on him later) sued the Browns owner for slander after

the owner told newspaper reporters that some of the Browns were playing poorly

on purpose to get traded. Pratt settled his lawsuit with the owner for an

undisclosed payment. It will give you some indication of the pro-ownership

slant of sports media at that time that Pratt was referred to as “the Browns’

Trotsky” for suing his owner.

3) Jimmy Austin was a future teammate of Eddie

Foster with the St. Louis Browns. Third base was really the only thing holding

the Browns back from winning a pennant for six or seven years in the late teens

and early twenties. Austin’s poor play at bat and in the field in 1922 and

other years prior, coupled with injuries, caused the Browns to claim Eddie

Foster off waivers. You can read my long winded essay on that here: http://flintfoster.blogspot.com/2018/07/the-right-man-at-almost-right-time.html

4) Although the popular nickname for Clark

Griffith was “Fox” or “Old Fox,” Griffith’s ballplayers called him “Teacher.”

Eddie Foster was himself responsible for this nickname, telling the Washington

Post in 1915 that “The Old Fox gets his players together every morning for a

talk, and Foster says it is worse than any school he ever attended.” Clark

Griffith was born and spent much of his childhood in rural Missouri, but his

family moved to rural Illinois after his father was killed in a hunting

accident. Griffith’s playing career had begun in the 19th Century

and ended in the early 20th Century. Griffith’s players liked to

joke about his playing days in the Civil War. They weren’t far off; by this

time, Griffith had already been involved in professional baseball in some

capacity for 25 years and had been managing for 16 years. In 1919, Griffith

bought a controlling share of the club owned the team until his death in 1955.

5) The Baseball Fraternity, also sometimes called the Players

Fraternity, was formed in 1912 around the time that a third professional

baseball league, The Federal League, came into existence. Much like the USFL

would do to football 70 years later, the Federal League would attempt to build

a presence by poaching players from the older, more established leagues with

large contracts. This gave the ballplayers bargaining leverage, which they used

in part to form the “Fraternity.” The Federal League went under for good and

forever in 1916.

6) When the American League and the National

League merged to form Major League Baseball in the early 1900’s, MLB was

governed by a Commission composed of the President of the National League, the

President of the American League, and a chairman of the commission who served

as the tiebreaker vote. Later events would eventually lead baseball to ditch

the three party Commission and appoint a single Commissioner of Baseball.

7) David Fultz was raised in Staunton, Virginia.

He attended Staunton Military Academy before attending Brown University. After

college, he played baseball with the New York Highlanders (now called the New

York Yankees) in the early 1900’s. The Highlanders’ Manager at that time was

Clark Griffith. When his playing career ended, Fultz became a lawyer. Former

teammates and other ballplayers approached Fultz about their contracts and

Fultz gradually formed the Fraternity from there.

8) Baseball’s ownership cowed less prominent

baseball players into signing. American League President Ban Johnson threatened

to throw Washington catcher (and college graduate) John Henry out of baseball

permanently for writing correspondence to other Major Leaguers requesting that

they join the strike. Only after Washington’s ownership and Clark Griffith

interceded on Henry’s behalf did Ban Johnson relent and let Henry play. Later

in the season, one Washington scribe cheekily referred to Henry as “the

Robespierre of the baseball revolution.”

9) Eddie Foster contracted typhoid early in April

1913 and was in the hospital for several months. He probably would’ve died

without the close care of his nurse, Nan Crismond, whom he would later marry.

10) From at least 1912 through 1916, the Senators

had training camp and played exhibition games in March at the University of

Virginia. In addition to having spring games between the starters and the minor

leaguers that they invited to camp, Washington would often play UVA’s baseball

teams. When the

Senators got off to a bad start to their regular season in 1917,

Charlottesville’s Daily Progress newspaper noted “The Washington ball club,

which this year passed up Charlottesville as a training camp, is next to the

bottom of the standing of the American League clubs, while Newark of the

International League, which trained here this spring, is now leading its

league.” While lauding Augusta in 1917, Griffith “still insist[ed] that

Charlottesville, Va., is the greatest place in the world in which to condition

ball players.”

11) Later

in that same game, Walter Johnson

hit a Yankee outfielder by the name of Birdie Cree in the head, knocking him

unconscious for five minutes.

12) As reported by one

of the Washington newspapers, “The last time Manager Griffith was invited to Cobb’s home for

dinner was in Detroit several years ago.” [1914] “Shortly before dinner time

Cobb excused himself, saying he was going to a store. This was before 6

o’clock. He did not return until 10:30 that night, and when he did it was with

a sprained hand and other marks of battle. It was the night of his long-to-be

remembered encounter with the butcher boy because of an argument the proprietor

of the shop had over the phone with Mrs. Cobb in regard to some fish she had

purchased.” Cobb went to the butcher’s shop, put a pistol to the butcher’s head

and told the butcher to call Cobb’s wife and apologize. The butcher did, but